by Greg Clough

One could argue that seed banks date back to the Neolithic age, 12,000 years ago when humans started farming and saving their best seeds for planting the next year.

While modern farmers tend to rely more on buying than storing seeds, the concept of seed banks lives on. However, today, it’s less about saving enough seed for next season’s planting than about surviving natural or human disasters or even global or nuclear crises. But more of that later.

Early 20th-century Russian agronomist Nikolai Vavilov was among the first to recognise the importance of seed banks. Vavilov feared for the future of genetic diversity. This fear was fuelled by the rise of large, state-controlled collective farms – the precursor of today’s “factory farms” – and their reliance on monocropping, the loss of traditional species to newer, domesticated and more productive crops, and the endless erosion of farmland to ever-expanding urbanisation. Critically, Vavilov saw genetic diversity as a solution to handling the almost seasonal famines that ravaged pre-Soviet Russia.

Domesticated crops, while more productive, surrendered too easily to natural disasters. They needed to be hardier. They needed greater diversity. They needed to be cross-bred with sturdy wild variants. Over 20 years, Vavilov established a seed bank in Leningrad – only to be arrested and sent to die in the Gulag for challenging Soviet ideology’s emphasis on environmental over genetic factors. In typical fascist revisionism, Vavilov appeared on a 1970s Soviet postage stamp, revered as a hero of the revolution. But he was neither hero nor villain. Merely a scientist searching for truth.

As important as preserving and expanding genetic diversity, seed banks are also important for safeguarding against the loss of endangered and rare plant species, particularly due to habitat loss. They can be reintroduced into restored habitats when secured in a safe place.

And, as Vavilov would approve, scientists and plant breeders use seeds from seed banks to create new crop types with desirable features, such as enhanced yield, nutritional value, or resilience to particular stresses – particularly, resilience to global warming. These improved species reduce the world’s reliance on a limited number of crops for global food security.

Seed banks are particularly important following natural disasters, widespread disease or human conflict. For example, a seed bank established in 1977 by the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas in Aleppo, Syria, has contributed significantly to restoring agricultural production since the start of the country’s civil war, saving an estimated 10 million people from hunger.

Seed banks also proved critical following the 1974 Rwanda genocide. According to the Head of the Center for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF), Éliane Ubalijoro, PhD, “When the genocide happened, people weren’t able to harvest their crops, so crops withered in the fields, and farmers couldn’t collect seeds from them to plant and harvest for the next year.”

Speaking on world food security at a recent conference held by Australia’s Crawford Fund, Ms Ubalijoro – born and raised in Rwanda – added that “when the (Rwanda) economy restarted, we needed to replenish the stocks of beans in the country. And because there were gene banks around the world that held copies of the genetic diversity of beans from Rwanda, we were able to restart.”

“People don’t understand the relationship between gene banks and what needs to happen when we have conflict or other terrible situations in the world and need to restart economies or restoration. It’s important to understand that gene banks are crucial to keeping hope alive, especially for our food systems and bringing back nature after major crises,” Ms Ubalijoro said.

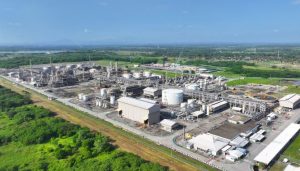

Today, some 1,700 seed banks are saving for our future. The more significant ones include the Millennium Seed Bank in the United Kingdom and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture’s gene bank in Colombia. CIFOR-ICRAF is home to one of the world’s largest tropical tree seed collections, with 192 tree species and 7,000 seed samples.

The biggest and most famous is the “Doomsday Vault”, more properly known as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, in Norway. According to the Global Crop Diversity Trust, the vault “holds more than 1.1 million seed varieties, originating from almost every country in the world.”

It is the Fort Knox of edible plant species. A vast, buried chamber of reinforced concrete and steel embedded in a permafrost mountain, the Doomsday Vault protects seeds and genetic material from all kinds of threats – man-made and non-man-made.

The vault can thwart earthquakes and tsunamis. It can prevent climate change, endangering seeds with rising temperatures and changing precipitation. It can preserve diverse seeds essential for rearing new crop varieties resistant to emerging diseases and pests and threatening food security.

During war and conflict, as noted above in Syria and Rwanda, it provides a secure backup of crop diversity to help nations rebuild their agricultural systems. And should that unexpected asteroid collide with Earth or, heaven forbid, a nuclear bomb explodes, the Dooms Day vault will be there to help us get started again.

Banner photo: Miguel Á. Padriñán/Pexels.com