by Nabiha Shahab

As the Earth’s temperature continues its relentless ascent, the global community grapples with the physical heat and the escalating political tensions that seem to mirror the environmental crisis. From the harrowing Russia-Ukraine war to the tumultuous power struggles in various African nations and the enduring Israel-Palestine war, the world appears to be engulfed in an era of unprecedented turmoil.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reported that since the beginning of this year, the global mean temperature for 2023 is the highest on record, 1.43°C above the pre-industrial average and 0.10°C higher than the 2016 ten-month average.

Amid these conflicts, the military sector is an often overlooked contributor to the increase of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In July, a Reuters report highlighted that significant GHG emissions originate from military operations. It cited a paper by international experts that the military sector accounts for 5.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions as the world’s biggest fuel consumer. The fact that the military sector is not included in any of the climate agreements, from the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to the 2015 Paris Agreement, may resulted in a skewed estimation of global greenhouse gas emissions. Failing to account for this crucial factor could undermine our efforts to combat climate change.

According to a 2021 United Nations report, the current pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are projected to result in an average temperature increase of 2.7 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, representing another alarming cautionary message preceding crucial climate negotiations.

Shifting priorities

Beyond emissions, the global conflict landscape also significantly affects resources. Pledges and initiatives intended to address climate change are at risk of being overshadowed by the pressing need for resources to alleviate the suffering caused by conflicts.

The pledges made under the Paris Agreement to allocate USD100 billion annually from 2020 to support states most vulnerable to the escalating impacts of climate change remain unmet, while pledges to support the wars and the consequential relief efforts for civilian casualties take centre stage.

Moekti Soejachmoen, Director of the Indonesia Research Institute for Decarbonization (IRID) said that “there are a lot of resources originally eared for the climate, now have to shift for the war (relief). This will significantly diminish the capacity to reduce emissions. The analogy is like forest fires – the carbon sequestered in the trees is released into the atmosphere, and at the same time, there are no more trees to absorb and store the carbon. A similar thing happens in wartime, you do not only have all the GHG emissions from the war but also have GHG emissions that supposedly can be reduced but cannot, due to less resources available to mitigate them”.

As the world witnesses a surge in both climate refugees and war refugees, the lines between these two crises become increasingly blurred, underscoring the intricate interplay between environmental degradation and political instability.

Continued popularity of fossil fuels

Moreover, the recent geopolitical tensions have led to unforeseen shifts in energy sources. The dependence on Russian gas in Europe has highlighted the fragility of energy security, prompting some countries to turn to fossil fuels as a stopgap measure, thereby dealing a setback to the collective efforts to transition away from carbon-intensive energy sources.

The expectations are mixed as the international community braces for the upcoming Conference of Parties (COP28) in Dubai. While the possibility of a breakthrough remains contingent on meaningful action to address fossil fuel consumption, a glimmer of hope exists.

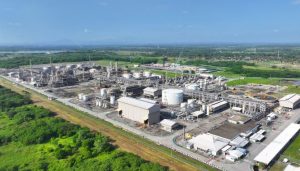

“There is hope of a breakthrough, most likely for technologies that can cut emissions but still support fossil fuel, such as the Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies. So the industries will have the best of both worlds, enabling climate mitigation but not killing the fossil fuel business,” said Soejachmoen.

Through collaborative efforts and stringent commitments to sustainable practices, it is possible to steer the course toward a more resilient and sustainable future.

Farhan Helmy, a researcher from the Thamrin School of Climate Change and Sustainability, conducted several simulations using the EN-ROADS climate simulator to assess various policies. He concluded that it is still feasible to meet the 1.5-degree Celsius global warming limit, provided that world leaders demonstrate unwavering commitment and refrain from prioritising the interests of groups that impede progress.

Helmy said that “there are still people or interest groups who persist with the old industry and try to stem it in various ways so that hinder progressive efforts. The urban areas, depending on the activities emit a significant portion of GHG emissions. Depending on the actors, for example, urban areas can play a significant role in reducing emissions by practising green industry. Secondly, also commitments at the corporate level, such as with the palm oil industry because it is driven by the market that has begun to pay attention to the climate crisis”.

In this critical juncture, global leaders and stakeholders must acknowledge the interconnected nature of environmental and political challenges. There is still time to lay the groundwork for a more stable and sustainable world by prioritising proactive measures that address climate change and conflict resolution. Time is of the essence, and the situation’s urgency demands swift, decisive action to navigate this unprecedented era of global boiling.