by Hartatik

The use of LNG will close the space for the use of clean and renewable energy, as is currently the case with coal. As a source of electricity, he continued, Indonesia has 207 Gigawatts (GW) of solar energy potential, but only about 0.1 GW has been used.

Greenpeace Southeast Asia-Indonesia’s Regional Climate and Energy Campaign Coordinator Tata Mustasya believes that the energy transition should be carried out with a direct leap from fossil energy to clean and renewable energy. Among the options are solar energy, which has abundant resources but is not being widely used yet.

“The transition to gas will not only not solve the climate crisis due to carbon emissions, although emissions from gas are lower than coal, for example, it will also delay the energy transition, which could take decades,” he said.

“Bali should also make an energy transition from coal-fired power plants to clean and renewable energy, but instead plans to transition to gas. Even though Bali has abundant solar energy potential.”

According to Tata, the cost of solar energy generation has fallen 90 percent over the past 10 years so that in some countries in Southeast Asia it is already lower than coal.

In Indonesia, a conducive incentive policy can make the economics of solar energy even better than coal and gas power plants.

He hopes that the government’s policy of choosing LNG as a transitional energy will not lead to delays in energy transition like those experienced under the coal oligarchy.

Avoid Environmental Conflict

Separately, Natural Resources Law Observer Ahmad Redi agreed that it is time for Indonesia to leave fossil energy and switch to new renewable energy. However, this new renewable energy cannot be used immediately, so there needs to be a transition.

Although the government took the policy to make LNG as a transitional energy, it must still prioritize environmental interests.

Developing LNG as a power source should not come with environmental risks such as damaging mangrove areas, protected areas and conservation areas, he said.

“So, LNG energy sources should be avoided in places that have the potential for massive environmental damage. For example (LNG terminals) in Bali must be considered again whether there is the potential for massive damage if it is still attempted,” he said.

But if it is still attempted, the place must also be able to control the impact of environmental damage.

“I think the environmental impact analysis must be done properly, so that the social, environmental and economic impacts can be calculated in the context of a good environmental economy,” the Tarumanegara University Law lecturer said.

“There should not be an LNG terminal [if] the environmental cost is high because it is not based on environmental interests. That would be a burden to the state.”

Meanwhile, marine biology expert Muhammad Zainuri, a professor at the Oceanography Department of Diponegoro University, said that although lower than fossil energy, LNG also produces carbon emissions.

“If CO gas is not captured by green areas, it will accumulate in the air and will form ions, molecules and atoms that fall with rain,” said Zainuri.

That may cause the sea to become more acidic and affect marine life as well as decrease photosynthesis, which would also affect water quality and temperature.

“If the temperature rises, the humidity will decrease. Humidity is the O2 and water content in the air that our bodies need. That’s why environmental experts disagree with the LNG project on the beach,” he explains.

Reducing Biodiversity

If photosynthesis is hampered, there will be less food for shrimp and fish fry, who may also fail to metamorphose, lay eggs and reproduce because of higher water temperature. That will also mean reduced populations of marine life in the area.

“If the water is hot, the sea becomes hotter and the amount of carbon increases. So there are two pressures so that life (in the ocean) is reduced,” he said.

LNG Infrastructure Development

Currently, the Indonesian government is focusing on increasing people’s access to electricity in all corners of Indonesia. The Indonesian government has targeted a national electricity program of 35,000 MW. Of the 35,000 MW, 38% of the electricity supply comes from gas with a capacity of 1,009 MMSCFD. 319 MMSCFD of gas is required to meet the electricity demand in eastern Indonesia. To overcome the challenge of delivering gas to power plant locations that are scattered and there is no pipeline gas network, natural gas needs to be converted into LNG to make it easier to reach the location of the power plant.

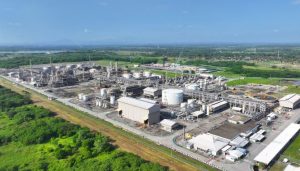

The government has built some LNG-based power plant infrastructure. The plan for infrastructure development is growing, with the planned construction of LNG/mini LNG facilities and the auction of LNG facilities, both in the Sumatra region, Central Indonesia, and Eastern Indonesia.

The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources has encouraged the construction of mini LNG terminals using truck transportation for remote areas not covered by pipelines since 2018. In 2020, PT Perusahaan Gas Negara Tbk (PGN) collaborated with PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) to provide LNG supply and infrastructure development in 52 PLN power plant locations throughout Indonesia.

Tutuka Ariadji, Director General of Oil and Gas at the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, said that the government offers ease of doing business and supporting facilities for investors, ranging from regulations, licensing, to fiscal and non-fiscal incentives to contribute in developing gas reserves. Currently, the largest gas consumers in Indonesia are industry, electricity, and fertilizer. Around 22.57% is exported in the form of LNG, and 13.13% is exported through pipelines. Total gas consumption reached 5,734.43 BBUTD.

To maintain energy security, Indonesia targets natural gas production of 12 BSCFD by 2030. Based on the Indonesian Gas Balance Sheet, it is estimated that there is a potential surplus to supply the needs of new industries in the country or for export. To meet domestic demand, especially for industry and power generation, the Indonesian government continues to increase infrastructure development, such as gas pipelines.

In addition, the development of small-scale and virtual LNG pipelines is also important to secure energy supply in certain areas with geographical constraints, such as on scattered small islands, especially in the eastern part of the country.

CEED’s study report on “Financing a Fossil Future, Tracing the Money Pipeline of Fossil Gas in Southeast Asia” revealed that Thailand and Indonesia are at the top of gas plant expansion. PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) has the largest number of gas power plants that have been built and proposed in Southeast Asia from 2016 onwards. Its 19 plants accounted for 67% of the total power plant construction using fossil gas.

“Gas development is progressing rapidly in SEA, more than five years since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015. This is because financial institutions are building reputations as enemies of climate and clean energy, rather than improving their energy and sustainability policies,” said Gerry Arrances, executive director of CEED said.

Part 1: LNG terminal construction sacrifices mangroves and the Bali marine ecosystem

Part 2: LNG Terminal construction in Bali: ‘No violation, just lack of information’

Foto banner: Representatives of indigenous peoples and environmental activists hold a demonstration against the LNG Terminal in Sidakarya, Denpasar, Bali, June 22, 2022. (Courtesy: Walhi Bali)

This story was published through the support of a joint ASEAN LNG Journalism Fellowship between Climate Tracker and the Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development